What Are Mutations?

Sometimes the instructions in a gene are different from the instructions needed to make a healthy protein. This happens because of a change in the gene, also known as a mutation in the gene. A gene can change on its own (called a spontaneous or de novo mutation), or a mutated gene can be passed from parents to children.

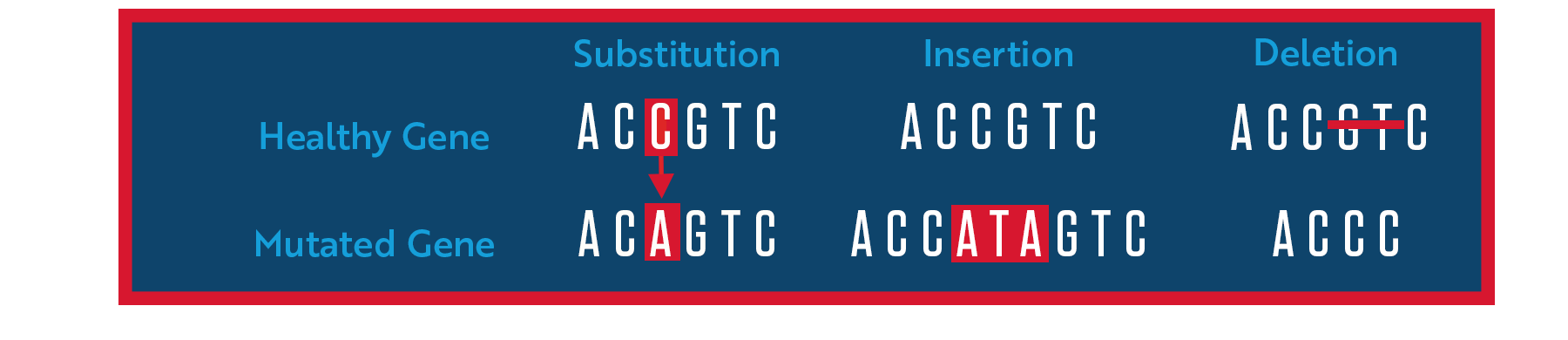

When a mutation occurs, it changes the letters (also known as a genetic sequence) that spell out the instructions sent to a cell’s protein-making machinery. Such “genetic typos” could substitute one letter for another or involve the insertion or deletion of one or more letters.

These changes can cause the cell to make too little protein, too much protein or a defective protein, depending on the mutation, which can be harmful to the cell and may lead to disease. The most common consequence of mutations in the genes that cause ALS is the production of a defective protein that becomes toxic. For example, researchers think that mutations in the SOD1 gene, the first mutations linked to ALS, cause neurons to produce a defective form of the superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) protein that has a new and toxic function.

Some mutations may be harmful not because of the proteins produced but because of their effect on RNA, a chemical cousin of DNA. One type of RNA, called messenger RNA (mRNA), is an intermediary, or messenger, between genes and proteins. To make a protein, the cell first uses the DNA gene to form an mRNA copy. That mRNA copy is then used to provide the “working instructions” to make the protein. After it is formed and before it is used to make protein, RNA is processed in several different ways. Mistakes in RNA processing may cause disease. For instance, the C9ORF72 gene may cause ALS due to accumulations of RNA that occur when the gene is mutated. FUS and TARDBP mutations may impair the normal processing of RNA from a wide variety of genes, leading to ALS.

Which Genes Have Been Linked to ALS?

The ALS Association has made significant investments into identifying the underlying genetic causes of the disease. This support led to the landmark discoveries of the SOD1 gene mutations in 1993 and C9orf72 in 2011, the most common gene associated with ALS.

Since then, multiple large, global “big data” initiatives supported by the Association, such as the New York Genome Center and Project MinE, have undertaken large sequencing and gene identification efforts, leading to the discovery of additional genes that are thought to cause or increase the risk of developing ALS.

Of the more than 40 genes that have been identified, four – C9orf72, SOD1, TARDBP and FUS – account for the disease in up to 70% of people with familial ALS, at least in European populations. Below you will find more information about these four genes, as well as a list of other genes that have been linked to ALS.

C9ORF72

Mutations in this gene are the most common genetic cause of ALS, accounting for between 25% and 40% of familial ALS cases (depending on the population) as well as approximately 6% of sporadic ALS cases. This gene also causes approximately 25% of another neurodegenerative disease, called frontotemporal dementia (FTD). Some people with the mutation only develop ALS, some people only develop FTD, and some people develop both diseases. How the same gene mutation can cause two diseases is not yet fully understood (although other genetic factors may play a role), and it is not yet possible to predict which will develop, or whether both will develop, in a person carrying the mutation.

The healthy function of the C9orf72 gene is still being studied, so its name refers to the position of the gene “open reading frame” on chromosome 9. The mutation in the C9orf72 gene that causes ALS is a hexanucleotide repeat expansion, meaning a six-letter repeated segment (GGGGCC) within the gene is expanded. The healthy version of the gene has about six of these hexanucleotide repeat units, while the disease-causing mutation has hundreds to thousands of them. Researchers are actively trying to understand all the effects of the C9orf72 expansion in hopes of designing treatments to mitigate them.

SOD1

Mutations in the SOD1 gene are the second-most common cause of familial ALS, found in about 10-20% of cases, as well as 1-2% of sporadic ALS cases. Researchers have identified more than 150 different mutations in the SOD1 gene linked to ALS. Each of these mutations influences the disease in different ways, most notably how quickly the disease progresses. In North America, the most common SOD1 mutation is called A4V, which is a shorthand way to say that the mutation changes the fourth amino acid in the protein from an alanine to a valine. The A4V mutation often causes rapid disease progression, although there are exceptions.

Healthy SOD1 proteins attach to copper and zinc molecules to break down toxic byproducts produced during normal cell processes. These byproducts must be broken down regularly so they don’t damage cells. SOD1 mutations are thought to cause the protein to misfold and clump up (aggregate) within motor neurons and astrocytes, the types of cells involved in ALS development and progression. These clumps (aggregates) may interfere with healthy cell functions or may cause other necessary proteins to misfold and lose their function. Researchers are looking for ways to prevent this aggregation.

TARDBP

The TARDBP gene contains instructions for making a protein called transactive response DNA binding protein 43 kDa (TDP-43). This protein plays an important role in keeping cells healthy. It attaches (binds) to DNA in the nucleus and regulates an activity called transcription, which is the first step cells use to create proteins from the instructions found in genes. TDP-43 is also involved in processing mRNA. By cutting and rearranging mRNA molecules in different ways, the TDP-43 protein controls the production of different versions of certain proteins.

Mutations in the TARDBP gene, which have been linked to about 4% of familial ALS and about 1% of sporadic ALS cases, cause TDP-43 to mislocalize in motor neurons, away from the nucleus where it is normally found and into the cytoplasm (the material surrounding the nucleus). In the cytoplasm, it aggregates into clumps that can be seen under the microscope. These clumps not only interfere with the important normal function of TDP-43 but also block other normal cellular processes. As more and more clumps form, they become toxic and eventually kill the cell.

Interestingly, clumps of abnormal TDP-43 can be found in almost all cases of ALS, even those without a TARDBP mutation, suggesting that TDP-43 may play a pivotal role in many forms of ALS.

FUS

The FUS gene provides instructions for making a protein called fused in sarcoma (FUS) that is found within the cell nucleus in most tissues. Like TDP-43, the FUS protein is involved in many steps of protein production. In fact, FUS and TDP-43 may interact as part of their normal function.

Mutations in the FUS gene are responsible for about 5% of familial ALS and about 1% of sporadic ALS cases. These mutations cause the FUS protein to mislocalize away from the nucleus and into the cytoplasm where they can aggregate into clumps and cause neuron dysfunction. Researchers are looking for ways to prevent this aggregation as a potential ALS treatment.

Other ALS-Linked Genes

With the accelerating advancement of technology, an ever-increasing number of new ALS-linked genes are being discovered each year. Below is a list of many (although not all) of the genes researchers have identified. The certainty that any specific gene is linked to ALS varies depending on the techniques used to identify the gene, the number of other studies that support its link to ALS, and whether the mutation’s biological effects are known. Genetic risk factors may also be different for different ethnic populations.

ACSL5

ALS2

ANG

ANXA11

ATXN2

ATXN3

C21orf2

CAV1

CCNF

CHCHD10

CHMP2B

CHRNA3

DAO

DCTN1

DNAJC7

ELP3

ERBB4

EWSR1

FIG4

GLE1

GLT8D1

hnRNPA1

hnRNPA2B1

KANK1

KIF5A

LGALSL

MATR3

MOBP

NEFH

NEK1

NIPA1

OPTN

PARK9

PFN1

PON1,2,3

PRPH

SARM1

SCFD1

SETX

SIGMAR1

SPG11

SPTLC1

SQSTM1

TAF15

TBK1

TIA1

TUBA4A

UBQLN2

VAPB

VCP

WDR7

Genetic Testing

The only way to know if you have a mutation in a gene associated with ALS is to get a genetic test. Depending on the test ordered by your doctor, it might be able to identify mutations in one to more than 20 ALS-associated genes. The decision whether to get tested or not is a very personal one. Genetic testing comes with many benefits, but also some risks, and may not be right for you. Click here to learn more about the benefits and risks of genetic testing for people living with ALS. If you haven’t been diagnosed with ALS but have family members with the disease, click here to explore the potential benefits and risks of genetic testing.